Dig it

On pain and pleasure in the archive

Sentiments induced by three hours on a late-opening Wednesday evening at the Bishopsgate Institute: enough to destroy my neck/back/shoulders for days. I’ve done the large-organisation desk-job before, I’ve done all the trainings, I know how my back and arms and eyeline and feet are supposed to align to make work not hurt. I have the DSA-provided desk chair, which I have to turf the cat out of every time I accede to the call of my body to please commit to sitting and working properly and break out of the denial-and-hunching-on-the-sofa neck-pain cycle, and then the cat stays bundled on my lap while I work which somewhat fucks with the whole posture thing anyway but I prioritise the emotional stability aid over the physical because the weight of his warm soft little body anchors me, like a diver’s lifeline, to what is good. What is precious and transcendent, among everything else that ebbs and flows, all the backwash, the riflusso,1 everything that hurts.

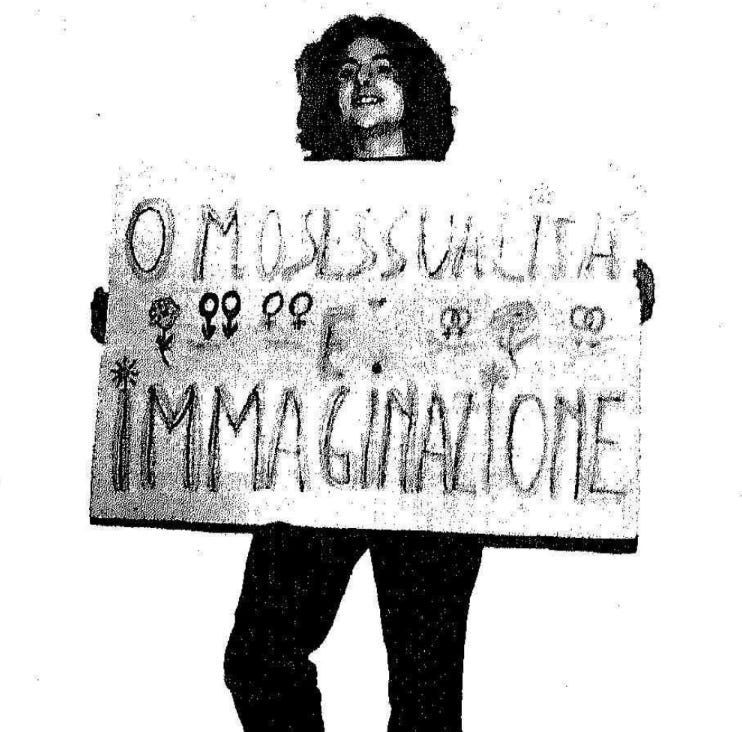

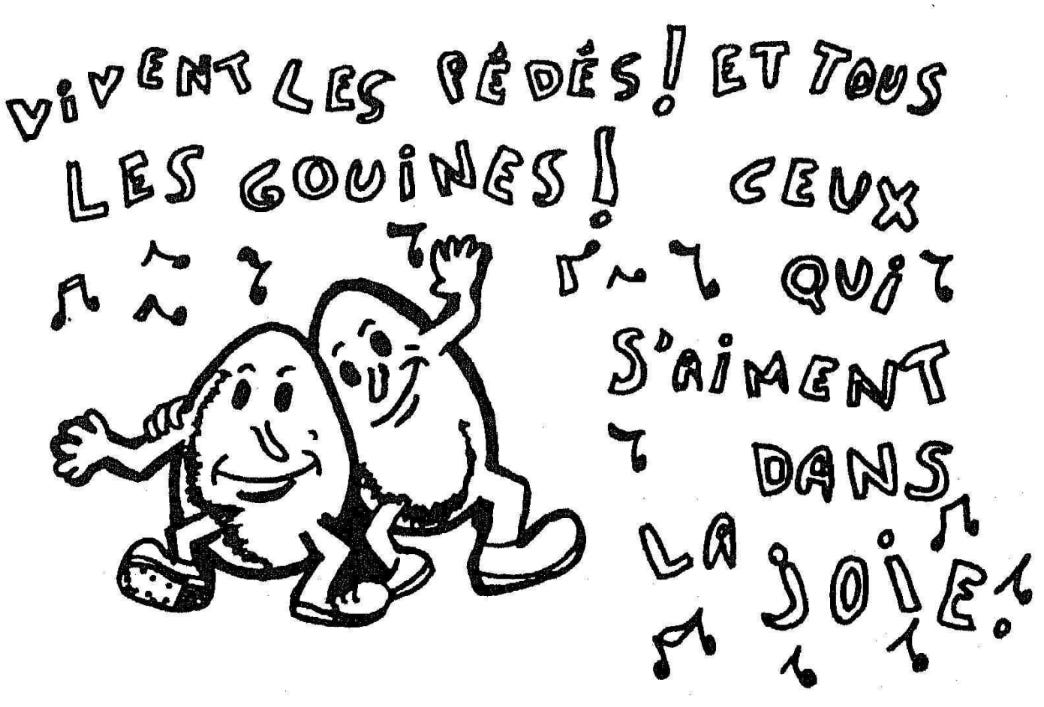

I’ve written here before about embracing the archive, and about how clarifying and transformative it’s been for me to work with Lola Olufemi’s conception of the Imaginative-Revolutionary Potential stored in objects of cultural production. The delicate, dialectical labour of understanding our archival materials within the subjective and objective context of their creation reveals how “a manifesto, a party programme, a diary entry, a placard, a sign […] contain in them the specific strategic, transformative, political goals and “hopes” that defined their inception.”2 We refuse the narrative of history, the teleology of the present,3 which erases these hopes with one hand while retuning them with the other in the key of their eventual ‘success’ or ‘failure’ — it doesn’t tend to matter which — as an irrelevant naiveté. “Our hopes,” writes liberationist militant Sheila Rowbotham, “have been appropriated, our aspirations twisted.”4 To defiantly retrieve them, to insist on their continued importance, she describes as touching the sources of desire.

He who seeks to approach his own buried past, says Walter Benjamin, must conduct himself like a man digging. Unearthing desire in the archive makes for a kind of contagious archaeology, releasing spores of imagination from the turned-over soil.

To ‘dig’, of course, pops up all over the anglophone archive of the ‘60s-’70s. Emblazoned across a page of the second issue of Come Together, the publication of the London Gay Liberation Front: DO IT IN THE STREETS DO IT IN FRONT OF THE STRAIGHTS IF YOU DIG IT DO IT. It’s one of my favourite idiosyncrasies, along with the ubiquity of “Right On”, accompanied in image or implication by a raised fist, sometimes invoked adjectivally as more-or-less-snarky meta-commentary: those ‘right on’ gays — 2025 synonym, woke.

(I just pulled the audio clip of the first time I consciously recognised the phrase from the depths of my memory and realised it’s in the Princess Diaries 2 movie: Mia thinks a prospective husband option is handsome, Joe tells her his boyfriend thinks so also, and Mia and Lilly put up the fist in unison, Right On.)

I think School of Rock — an infinitely superior, some might say flawless, movie — was my earliest reference in life for ‘dig’: they’re gonna dig you, I swear (#affirmations). But suddenly there’s a dig it knocking around in my brain like a DVD logo and it doesn’t take long to tease it out, because of course it’s Diane di Prima, and of course it’s this poem:

… THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION

THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION

THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION

ALL OTHER WARS ARE SUBSUMED IN IT…… dig it

there is no way out of the spiritual battle

the war is the war against the imagination

you can’t sign up as a conscientious objectorthe war of the worlds hangs here, right now, in the balance

it is a war for this world, to keep it

a vale of soul-making…—Diane di Prima, Revolutionary Letter #75 (Rant)

Jackie Wang nuances: I don’t believe the imagination can fix everything (I am a rigorous materialist!), but it can do some of the work: the work of creating openings where there were none. But then I suppose di Prima didn’t say that the imagination could fix everything, either; just because something is under attack, must be defended, must be exercised in defiance of its attempted exorcism, doesn’t make it the one true instrument of victory. After all, NO ONE WAY WORKS, it will take all of us shoving at the thing from all sides to bring it down.

But this is what drew me to gay liberationism and the post-’68 moment in the first place: they are saturated with imagination. They bathe in it. In this analogy our current landscape of capitalist realism feels like some Mad Max: Fury Road shit. (Do not, my friends, become addicted to imagination. It will take hold of you, and you will resent its absence.) In this desert of the real, di Prima’s Rant rings out: history is a living weapon in your hand.

“We are historians,” E.P. Thompson famously proclaimed, “because we know that the past is not dead, inert, and confining, but is strong with energies which can be brought once again to our side.” It is incumbent upon us as historical materialists to approach the archive accordingly: our sacred task to harness these energies, mobilising their contagious eruption into the overwhelming stasis of the present, of capitalist realism, to break open what is and supposedly must be with the power to imagine something different.

Touching the sources of desire. We know when we’re doing it right because we find it impossible to remain, ourselves, untouched. The subject/object relationship explodes and reforms and explodes again like a kaleidoscope. This relates to what Elizabeth Freeman delightfully calls ‘bottom historiography’; the receptacle of queer history receives “a transmission of receptivity itself, of a certain pleasurably porous relation to new configurations of the past and unpredictable futures.”5 And then the only thing left to do is to become vectors of contagion. Freeman, specifically, wants to advocate for the historiographical function of pleasure, against the generalised presumption of “melancholic queer theory” that pain “is the proper ticket into historical consciousness.”6

I, too, am trying to puncture the hegemony of the melancholic in approaches to queer/trans history — without judgement; without misunderstanding or disrespecting its origins; simply saying, it is time for something new, something old-as-new, same-and-different; simply saying, we urgently need something more. Keywords from the gay liberationist archive: joy, life, desire.

But still the archive hurts.

One of the reasons for my Substack sabbatical was a mad rush of writing for my end-of-first-year progression review, of trying to marshal the kaleidoscope into sufficient coherence. On archival/historical methodology, I wrote:

Building on Lauren Berlant’s description of desire as “a state of attachment to something or someone, and the cloud of possibility that is generated by the gap between an object’s specificity and the needs and promises projected onto it”,7 Olufemi frames that ‘object’ as liberation; she seeks to “reproduce that “cloud of possibility” for others, arguing that engagement with cultural production ignites the imagination which strengthens a desirous attachment […] a liberatory structure of feeling” from which actions of resistance bloom.8

In chorus with these aims, I also want to probe other desirous relations that can be examined through Berlant’s framework: for one, our attachment as researchers and revolutionaries to the ‘object’ of the archive, as it fulfils, disappoints, surprises, and transcends our desiring projections. And — less obviously perhaps — vice versa. The writers of these texts and collectors of these objects, and (separately or not) their depositors in the archive, project needs and promises onto us, too: their readers, their researchers, their spectral avatars of the queer/trans/liberated future.

They desire us, and they desire something from us, and from our conditions of possibility — something fulfilled, disappointed, surprised, transcended, betrayed. Touching the gay liberationist archive means partaking of a mutually desiring relation where the play of similarity and difference constellates complexly with affective currents of both melancholy and excitement/pleasure. It means entering the cloud of possibility in which we feel, know ourselves to be, triumphant and devastated at the same time.

In other words, I appreciate Freeman’s exploration of the pleasure in how “we are “bound” to queer successors whom we might not recognize”; I just would venture (and not unfaithfully to the kinky spirit of Freeman’s formulation!) to reintroduce the pain as well. Through and beyond the pain of the distance, the pain of everything and everyone lost between their world and ours, the protagonists of the archive disappoint our desires, and we disappoint theirs — and that’s before we even start to think about the vast and exquisite field of unpredictable, mutually disappointed desires expanding out from ourselves to the queers of the future.

The above question was prompted by relating strongly to - and frequently finding methodological comfort in - Benjamin’s mode of digging. True, he writes, for successful excavations a plan is needed. Yet no less indispensable is the cautious probing of the spade in the dark loam, and it is to cheat oneself of the richest prize to preserve as a record merely the inventory of one’s discoveries, and not this dark joy of the place of the finding itself. Remembrance, history, can be no dry narrative report; it must be epic and rhapsodic.9 The joy is not subordinate to the finding. It is joyful simply to be the one who digs; who turns the soil, throws up the spores of imagination; who partakes in that receptivity — that pleasurably porous relation.

But what about when we don’t like what we find?

Fruitless searching is as much a part of this - the dark joy, that is - as succeeding, says Benjamin, but what about when we do find fruit and find it not simply unpleasant but spoiled, rotten, putrescent, when it makes us want to stop digging — to leave it in the dark, to let the soil break it down into indeterminate compost — because we fear what spores might be released if we dissect it in the open, in the light? The initial finding is unexpected, the discovery uncomfortable; like finding one mouldy strawberry in the box and paranoically checking all the others to be sure they haven’t yet been ruined. But the rotten fruit is not ultimately surprising or alien: I know something of the trees it sprouted (from); I recognise the weapons mobilised in the name of uprooting those trees, and the war-machines those weapons became; and I want no part of either.

This kind of pain is wrapped in nausea, obviously, and also in resentment. Like, I came here for the excitement, the eroticism, the dark joy of finding, the imaginative-revolutionary potential, and you tricked me and now all I have is an upset stomach to add to my aching back and blistered hands from all this fucking digging. And, worse, a doomlike sense of existential responsibility with no possible resolution.

They disappoint our desires. We wish they had been more cynical, sometimes. That they had opened certain windows for contestation with greater caution, just a crack — instead of throwing them wide open, so that we are forced to concede to the wisdom of slamming them shut even though we know where it comes from and what it serves. Resentment!!!!! of having to cede ground to immunitarian logic, limit the porosity, triage the energies, take prophylactic measures against the contagion — not because I disagree with, even condemn, what I’m imbibing (indeed these apply to plenty of the findings which nonetheless inhabit me most fervently and even most joyously), but because it’s making me sick.

The archive hurts like this, sometimes, just sometimes, at its worst. But it is also mercifully contradictory, full of its own discordant, synchronous critique. Gay liberationists consistently decried the false tolerance of the newly ‘sexually liberated’ society, which superseded the old order of prudish silence by boxing up their perversions to great fanfare and selling them back to them. This kind of tolerance, this repressive desublimation, was in many ways worse than the sublimation it replaced; at least with intolerance you know where you stand, the experience of alienation is shared, there is a wall to be dismantled together. Tolerance is sneakier; it’s not liberation, but it can pretend to be, can even gaslight you into feeling like it is, into feeling like what you’re feeling is what liberation would feel like.

From this perspective, the orthodoxy of tolerating everything except intolerance is already on shaky ground. So the painful lesson shouldn’t be a shock: that there are, actually, things one should not tolerate — things that have relatively little to do with ‘intolerance’, can even weaponise accusations of intolerance in their own defence, because ‘intolerance’ is far from having a monopoly on violence and on subordination. Tolerance and intolerance are two sides of a coin that we/they flipped and watched fall into the abyss. Here there are no horizons.

We disappoint their desires in turn, which is another way the archive hurts. I mean, in this instance (to give us a little more grace), the ‘we’ of our world, our society, our conditions of possibility — things over which we have little control, and feel even less than we do have. This field of pain is peppered with specific forms of melancholy, forms that make you want to invent German words that probably already exist. There’s something from somewhere about nostalgia for things you never lived.

What I mean to say is: I pore over the archive and wish I believed in something. I wish I believed in a revolution within our lifetimes. I wish the things about which I could say “when” instead of “if” were not all hopeless things.

Thesis VI: To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. Historical materialism wishes to retain that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to man singled out by history at a moment of danger. The danger affects both the content of the tradition and its receivers. The same threat hangs over both: that of becoming a tool of the ruling classes. In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it. The Messiah comes not only as the redeemer, he comes as the subduer of Antichrist. Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

— Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’

I went searching for a gay liberationism that would escape and burn the hands of the system attempting to wield its origins against us;10 I went digging in the light of the flash of danger, which I just had to backspace and retype because muscle memory had me start it as ‘gender’. Look-to-camera moments like this come more and more often these days — you know what I mean. Moments that have you like, okay, we GET it. Someone give the writers’ room a lesson in nuance already. No-one wants to watch a show this overwritten. Like switching tabs from an archival snippet about the scapegoating of the homosexual in the Italian press, straight into the witch-hunt for transgender ideology in the assassination of Charlie Kirk; ‘they direct the attention of ‘normal people’ to find in homosexuals and other minorities the root of all evil’.11 Tale as old as time — no need to make it quite so obvious.

There’s less visceral nausea in this type of pain. Resentment perhaps, floating, but hard to sustain without an of. And who to blame? Just a litany of tiny cogs; no point to it, no heart for it either. Instead the pain comes like a wash of a terrible nothing that encompasses everything, suffocating. The war is the war against the imagination / the war of the worlds hangs here, right now, in the balance / this enemy has not ceased to be victorious. Encircled by a yawning maw of eldritch horror yet sooooooo fucking banal at the same time, and the awareness of the banality of being swallowed by the horror fuels a new kind of horror which is immediately chewed up and vomited out into a new kind of banality that is also always the same.

The ironies do, at least, speak too loudly not to gestate a measure of grim humour.

Here, too, the archive speaks back.

… seesaw voyage vectorial voyage voyage with possible departures and arrivals undulating voyage through un-written history to gather up the thread of lost humanity, to gather yesterday’s tears into tomorrow’s eyes, to find a laugh that is also a cry and a cry that is a synchronous laugh, find a cry and a synchronous laugh,

FIND THE SYNCHRON(ICIT)Y OF HISTORY

— Giuliana Cabrini, ‘Eros diffuso’ (Fuori! No. 10, Summer 1973)

I am trying (god damn it!) to argue against the monopoly on melancholy in the queer archive. Not against the melancholy — against the monopoly. I’m trying to open a window to something else. Some days that window feels like the only escape from a burning building. Some days I am dragging myself there across the floor, nose to the carpet, trying to catch the last bits of breathable air. This is a very self-indulgent way to feel (never mind self-important). Self-indulgence in dissociated misery is much more accessible these days than self-indulgence in embodied joy. We know too much, and too little. Brain like an overcrowded A&E but no medical training, only a whiteboard on which to scrawl, YOUR BODY IS MORE THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS. Everyone is in too much pain to read it.

“…that is, the squalid period in which many have reneged on the revolutionary “vocation” they claimed to have discovered in ‘68 or in the years immediately following. The riflusso has submerged great vital instances that emerged in those years and were immediately sucked back into politics… it is not only an Italian phenomenon: it manifests wherever the subversive and emancipatory impulses of the ‘60s and ‘70s have been blocked – wherever the domination of capital is no longer challenged by living voices and movements.” This is Mario Mieli’s gloomy reflection, in the 1982 foreword to the Dutch translation of his 1977 Elementi di critica omosessuale, on the pessimism that had taken fuller shape in the intervening period. Like others, I render riflusso in Italian due to its untranslatability. It is best captured in English by a fusing of ‘flow’/‘ebb’/‘backwash’/‘backlash’ on the one hand, and ‘reflux’, as in acid reflux, on the other.

Omolola Olufemi (2024), ‘”But... the luminous tree!” The Uses of the Imagination in Resistant Cultural Production’ PhD thesis University of Westminster, p64.

Kristin Ross (2002), May ’68 and its Afterlives. University of Chicago Press, p2. Jesus this is such a fucking good book.

Sheila Rowbotham (2001), Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties. Penguin: London, pxv.

Elizabeth Freeman (2005),‘Time Binds, or Erotohistoriography’, Social Text 23 (3-4 (84-85)), p64.

Freeman, p59.

Lauren Berlant (2012), Desire/Love. Punctum Books, p6.

Olufemi, p57.

This whole digging metaphor is from Benjamin’s Berlin Chronicle, cited here from the collection Reflections (1986), New York: Schocken Books, p26.

One of the founding members of the Gay Liberation Front in London in 1970 went on to found the (transphobic, for those blissfully unaware and in case the name didn’t give it away) LGB Alliance in 2019.

From the transcript of a meeting held between members of FUORI! (Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano), the Italian section of the Fourth International, and Lotta Continua: ‘Omosessuali e sinistra extra’, Fuori! No. 11 (Winter 1973).